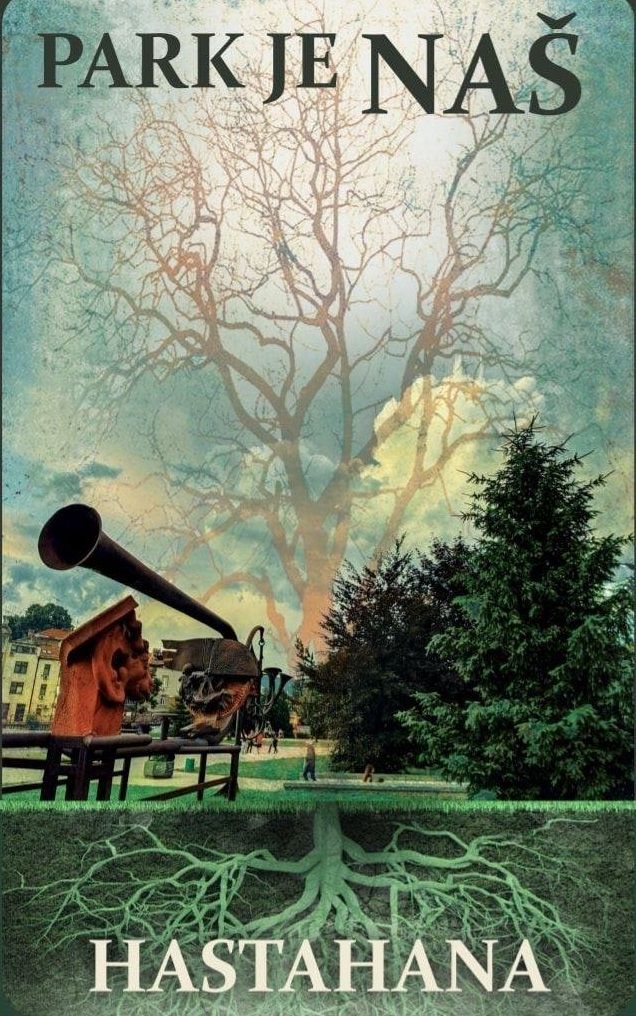

The fight over a park(ing) area in Sarajevo has raised art activism to rescue not only a sculpture, but also rare green space in the city. On August 5th, city workers started to dismantle Helmut Lutz’ sculptural installation Sternenweg (Road under the stars) in Sarajevo’s Hastahana park without announcement before citizens and members of the Hastahana Park initiative interfered, astonished by their unprofessional action. Though for a while the carelessly disassembled pieces remained abandoned on the grass, actions by artists and citizens have fostered a discussion of what was supposed to be handled clandestinely.

The dismantling of this fantastic, fairytale-like installation was the first implementation of the transformation of Hastahana park in Sarajevo’s center, officially renamed Nijaz Duraković park in May 2018. Yet park might not be the correct designation for the future area on which a multi-story building including an underground garage, art pavilion, local community premises and other social facilities are supposed to be built. The area of Hastahana park only spans about one football field. Space for greenery and trees is minimized for the sake of underground parking lots and a three-story building, which will probably be used as a shopping mall. The municipality, claiming that the neighborhood needs more parking space, presented its proposed combination of a park, underground parking and a building in a seductive 3D animation in April 2019 (available online). Indeed, the question of car space is important in Sarajevo. Yet the issue is rather that the city has too many cars than lack of parking space. Instead of investing in public transport, new multi-story parking garages have been built in the last years, which often remain half-empty as they are too expensive for the average citizens.

In contrast to what authorities have claimed is a necessary future for the former Hastahana park, citizens of the neighborhood Marijin Dvor have different demands. In their view, Sarajevo is in desperate need of green space. Only around 1,5 % of the city is designated green space, which makes the residents’ call for the Hastahana Park and No Concrete! all the more understandable. In videos, online on Hastahana Park’s facebook and instagram page, citizens articulate their wishes about the future of the park, which they believe belongs to different generations of Sarajevo, children, young people, pensioners. Let’s make the park into a true park, do not let the concrete take that place. The artist Damir Nikšić has addressed the struggle for the park in a music video in which he sings We are defending Hastahana with members of the Hastahana Park initiative.

The urban transformation in Sarajevo in the last 25 years has focused on lucrative investment rather than smart infrastructure and public green space. Air pollution has increased immensely since new high-rise buildings have prevented proper air circulation. Coupled with the use of highly-polluting vehicles, new records of air pollution have recently made Sarajevo to one of the most polluted cities worldwide. Causing damages in organs and cells of the human body, possibly resulting in dementia, heart disease, fertility problems and reduced intelligence, it is estimated that annually, more than 3,300 people die of air pollution-related illnesses in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It is clear that Sarajevo is in need for a green lung rather than yet-another parking lot likely to not be taken advantage of fully. The maintenance of Hastahana park as a green space is not only a literal way of contributing to Sarajevo’s necessary turn to sustainable urban planning, but symbolizes far more. It should be seen as resistance to a sick and corrupt political system that prioritizes profit over citizens’ needs. Even though the residents of the neighborhood have repeatedly articulated their demands in many public ways, it is as if they are running against windmills. Since the initiative Hastahana Park was formed two years ago, members have dedicated their free time and energy to public campaigns and organizing meetings, hoping to influence the future of the park. And, recently, they have begun to protect a sculpture that found its home in the park. The artist Helmut Lutz had donated it to the city of Sarajevo, aiming to connect people across borders, for reconciliation and for a better future after Sarajevo had endured a siege of almost fours years (1992-1995) during the Yugoslav War.

Lutz’ sculpture is full of symbolic attributions. It encourages the visitor to interact with it, working on bringing people together also physically. The tree of life is centered in a spiral, topped with a crown of fruits and ear shells, referring to Adam and Eve in paradise. The heads of a snake and a dragon function as a lever to open the crown. Flanked by stone books from which figures step out, it depicts the path of humans as a continuous way of healing. Icarus’ wings move when you pedal and turning bollards make the human figure disappear and a Minotaurus emerge. According to the artist, the references to Greek mythology open a way of understanding Europe’s legacy east of it.

The artist has dedicated his life’s work to establish connections beyond borders. As part of his West-East-path initiative, he created his first sculptural installation Sternenweg between 1978 and 1982 in the German town Breisach, bordering France, in order to strengthen German-French relations. Before he donated the sculpture Sternenweg to Sarajevo in 2005, it had already journeyed across Europe, Istanbul and Jerusalem, meant to link the so-called East and West, promoting intercultural dialogue. At each station the sculpture was accompanied by dance and music performances including fabulous stage sets and costumes. In 1995, when Lutz was prevented from bringing his installation to the former Yugoslavia due to the outbreak of the war, he dropped a wooden sculpture into Danube in the Hungarian town Mohács, stating Europe is crying. The message was to be taken by water, freely crossing borders, up into former Yugoslavia.

The sculpture Sternenweg stands for healing, symbolized through the shell. Already in 2000, Lutz’ so called soundship Im Augenblick (In the moment) had been set up in front of the railway station of Sarajevo, which was still marked by the scars of the wartime shelling. It must have been a moment of great hope and enthusiasm when Markus Stockhausen, trumpeter and composer from Germany, played on it together with colleagues from Sarajevo, the trumpet player Denis Amitović and trombonist Marin Gradac. The founder and director of Sarajevo Jazz Fest, Edin Zubčević, in the article The Vandalism and The Renaissance recalls how he was astonished by the futuristic ship that seemed to have escaped from a novel of epic fiction or a dystopian film.

For the artist Lutz the place assigned to the sculpture in 2005, when the city authorities placed it in the Hastahana park, aligns perfectly with his aim to symbolize a way of healing. Hastahana translates to hospital (from Ottoman Turkish خستهخانه, hastahane). On the site of today’s park, the Ottomans founded Sarajevo’s first public hospital in 1866, military hospital as part of the Gazi Husrev-beg Waqf, a charitable endowment. In an action to draw attention to continuity of name and function, Lutz initiated a medical congress, financed by Aeskulap, a manufacturing company for medical devices, in Sarajevo in 2008.

When he was informed about the unannounced removal of his sculpture at the beginning of August, he was shocked, as he stated in an interview with the author. He received the information not through the authorities, which began the removal without the artist’s consultation, but through the initiative Hastahana Park. Since then residents, activists and artists have drawn much attention with their protest against the sculpture’s dismantling. After interrupting the attempted removal by city authorities, they launched a spontaneous intervention by wrapping foil around the disassembled pipes to protect the sculpture, vulnerable in its disassembled state . As part of this intervention, the artist Mak Hubjer sprayed a letter on a piece of wooden panel addressing Lutz with the words Dear Helmut, thank you and goodbye, Yours Sarajevo. In an interview with the author, Hubjer stated that the Hastahana Park is a representation of the citizen’s fight for public space, and that the collateral damage done to the sculpture of Helmut Lutz pertains a broader issue considering the behavior of the political elite. For him, Hastahana park is a symbol of the people feeling that they own something, that they are part of something and on the other side there are investors that want to build a building.

One day later the Sarajevan collective Odron held a symbolical funeral procession for the park. People wearing black assembled around the sculpture’s remains and led a black coffin in their procession through the surrounding streets. The media attention was high and members of the collective expressed satisfaction in their contribution to exert pressure on city authorities, which had been cautious to take further measures since the citizens displayed their resistance.

However, at the point the authorities of the municipality began to be cooperative for many days the parts of Helmut Lutz’ sculpture had already been laying bare and unprotected on the park’s grass, making it susceptible to vandalism and theft. The former mayor of the Center of Sarajevo Nedžad Ajnadžić answered the letter Helmut Lutz had sent to the citizens of Sarajevo stating his intention to involve the artist as well as the German Embassy in the process of the sculpture’s relocation. He promised the re- installation the sculpture in the remaining park space once construction will be finished. While past experiences make it difficult for Sarajevo’s citizens to trust in the assurances of politicians, the newly gained attention to the issue of the park, even internationally, created hope. Since more eyes are watching the events, the city authorities no longer can act without repercussions. The sculpture was lately rebuilt under the supervision of the artist’s son. This is only an interim measure, as in March next year the sculpture is to find a temporary new location in front of the SCC shopping mall when construction work on the park is due to begin.

Recently, the Hastahana Park initiative has begun to collaborate with a group of architects, surveyors and other professionals in designing a counter-plan to the 3D animated rendering of the park(ing) area, following a survey among the residents and taking into account the scale of the area and feasibility. Even if the fight to protect Lutz’ sculpture as well as one of the small remaining green spaces in the city is not yet ended, the interference that was achieved through interventions of citizen initiatives and artistic collectives has confirmed once more that art has the power to make change, to mediate and to disrupt. Realizing the plan by the Hastahana Park initiative would not only retain the park’s function as a green space in which citizens can rest, play, hang out and do sports, yet would also confirm citizens’ democratic ability to use their basic civil rights to foster change. This will hopefully pave the way for a more participatory society by challenging political decision makers in their habit to act behind closed curtains.